Lessons from 3 years living in 4 communes

I helped set up a commune in New York City in 2015, and have stayed in three others for periods of time in San Francisco. I’ve been so happy with the lifestyle that I’d like to live in a commune for the rest of my life. (This feels like a bold pronouncement to type. Yet plenty of people make life commitments, like marriage, at my age, so I might as well make a lifestyle commitment).

By pooling resources and sharing chores, I save thousands of hours and dollars a year. But the practical benefits are only a small part of the story. I’ve met friends, business and romantic partners through the commune network, and feel like my life is immeasurably richer for having shared it with a larger community. And in a world where we’re going to continue to have more people and finite resources, we could all afford to get better at sharing.

If you’re curious about whether commune life might be a fit for you, I’ve compiled a list of answers to FAQs here, based on a talk that I gave jointly with Michael Lai (of The Archive) at the RISE retreat in March 2018.

What are we really talking about?

Though they go by many names — co-ops, co-living, co-housing, kibbutzim, intentional communities — I use ‘commune’ to describe a set of adults living together by choice rather than economic necessity, where any ‘profits’ made are shared by the community. (To be clear, I’m not talking about people sharing their personal incomes, only any surplus the house might have).

How is this different from simply living with roommates? Some use the term ‘intentional communities’, to convey the roommates’ desire to live by certain values. These may range from ‘live with people who will inspire me to be better at life’, to pages-long documents outlining the commune’s mission, like these examples from The Archive and Agape.

I also use the word commune to distinguish from venture-backed coliving communities like WeLive and Common. While I’m delighted that these companies are getting funding and growing, they are ultimately hospitality companies that manage the experience of those who live in their properties. A commune tends to be self-managed, more like a co-op. But unlike co-ops, which at least in New York real estate terms describes a group that co-manages an apartment building but largely lives separate lives, in communes the residents share the majority of their space and resources.

Why would you choose to live this way?

The New York Times, in a 2013 piece on the rise of Bay Area communes, quotes Nick Lane-Smith of The Sub:

“You get to come home every day and it’s like opening a cereal box with a toy inside. You have no idea who’s going to be over and what they’re going to be doing and who they brought with them that you get to meet.”

How you react to that quote might be a good indicator of how you’d like commune life. It’s not for everyone. But most people’s aversion to commune life comes from misplaced fears: that you will have nightmare roommates, that you won’t have any privacy, that you’ll be judged for living in an ‘arrangement more typical for people in their 20s’ (according to another NY Times think piece). To the first two concerns, I’d argue that a well structured commune will render them moot; to the last concern, I’d say that people who would judge you for this lifestyle aren’t worth your time.

If you’re moving in with people with more maturity than the average college student, chances are you’ll find commune life brings more benefits than costs. A few illustrative anecdotes:

- I got into a bad bicycle accident in San Francisco, 3,000 miles from my family and my primary care physician. After I got out of the ER, my roommates in the commune I was staying in at the time rallied to take care of me, buying food, checking in on me multiple times a day, even helping email members of my team to tell them I’d be out of commission for a few days.

- The Archive, a commune in San Francisco, realized its members collectively spent over $10k a year on gym memberships and fitness classes, so invested a fraction of that into a home gym setup that rivals The Rock’s Iron Paradise, including weights, Peloton, and a sauna.

- At Gramercy House, the commune I cofounded in New York, some of the rooms are the size of studio apartments, and offer plenty of space to retreat when you want alone time — but you also have 1500 sq ft of entertaining space, more than any of us could afford in central Manhattan on our own.

- Residents of The Embassy, a commune in San Francisco, use the time and $ freed up by living collectively to prototype different governing structures and give back to their neighborhood: they practice and publish research on alternative justice, engage with formerly incarcerated members of the community (and host games of Dungeons & Dragons with them), and offer free childcare at all of their events.

Basically, if you want emotional support, nicer amenities than you’d be able to afford on your own, and/or to build an alternate utopian way of life, consider living in a commune.

Who lives in communes?

To many, the word ‘commune’ evokes a smoky den of drug-addled hippies who all sleep with each other. There are still communes for those kinds of experiences, but for those who worry they might not fit in, these days there are communes suited to a vast range of lifestyles. Gramercy House is home to a lawyer, a writer, a design director at a large startup, and a VP at a blockchain startup, for example.

As Melissa Kwan, my cofounder at Gramercy House, puts it:

People who choose this lifestyle are people who no longer value privacy the same way: these are people who are willing to give up a few years or more of “privacy” for the sake of learning from other people and having their boundaries pushed.

People tend to flock to communes with people around the same age, though I’ve lived with residents as young as a couple months and up to mid-60s.

How big are communes?

Gramercy House is on the smaller side, with five private bedrooms and a large living and dining room spread over two floors. The largest commune I’ve stayed in in San Francisco houses 24 people, but I’ve visited others with more than 50.

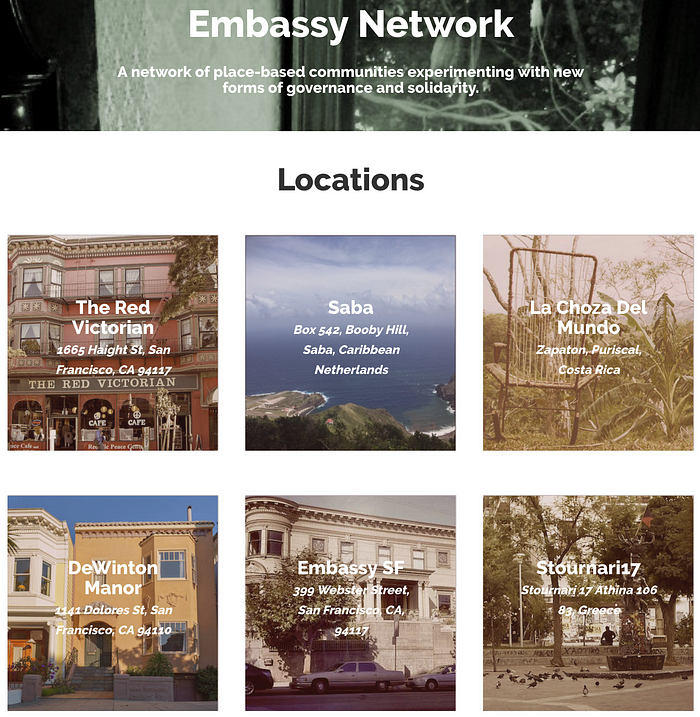

Many communes join together in federations with shared values, infrastructure, and/or legal ties. For example, the Embassy Network is a collective of 10+ properties around the world that utilize an open source software called Modern Nomad to manage the properties (more on that below). Haight St Commons is an informal network of communes in San Francisco that share insights and best practices, but no legal or financial ties.

How do you decide who joins?

This is a matter of personal taste above all else, but a few best practices for adding new members:

- Have an agreed-upon set of values, ideally in writing. Like a marriage, you never enter into a relationship expecting the worst, but you should be prepared in case someone’s behavior differs wildly from expectations, and have a mediation/exit strategy that’s been agreed upon in advance.

- If nothing else, have a legal sublease agreement.

In Melissa’s words:

It’s easy to get caught up in the excitement of creating a new community or the addition of a new roommate, but it’s just as important to think about the exit scenarios because that is the thing that causes the most complications and hostility.

As for the actual recruiting process, I’ve seen everything from written applications reviewed by a central ‘committee’ to a completely decentralized model where the outgoing resident is expected to find his/her replacement. Again, it’s a matter of personal taste. However, some common screening questions are below. There’s no right or wrong answer, but it’s important that everyone in the house understands and respects each others’ boundaries.

- Is it ok for a friend of another resident to stay in your room if you’re not around?

- how late do you tend to stay up and how much noise do you tend to make?

- how often do you intend to host people, both for events and guests in from out of town?

- what hours do you expect to be around home?

- Is it ok for your roommates to turn your room into a museum/shrine if you’re not around for an extended period of time? (ok, maybe this doesn’t need to make it on to the regular screening list)

How much does it cost to live in a commune?

Ongoing costs (we’ll cover startup costs in the next section) will include rent or a mortgage, utilities, cleaning, maintenance, common supplies like toilet paper and dish soap, and maybe a food share or ‘fun fund’ that goes to community-building activities like shared meals or events.

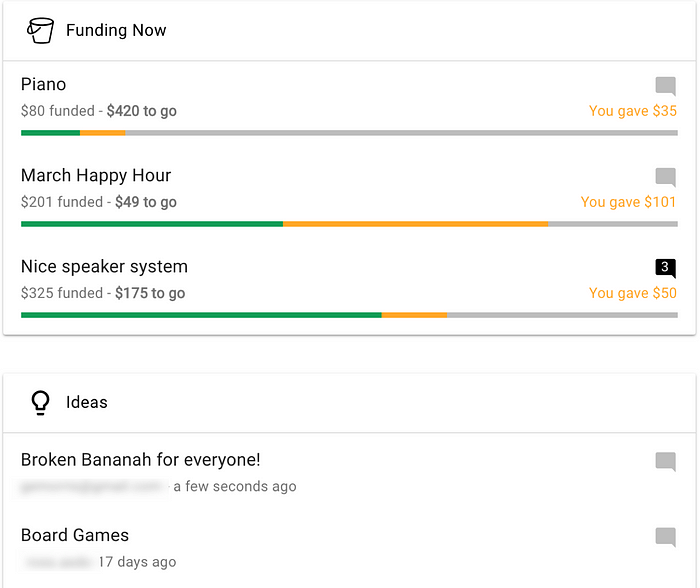

After experimenting with different models, none of which worked well, we’ve structured sublease rates at Gramercy House so our fixed ‘income’ from rent includes enough buffer to pay for all necessary house expenses, put money in a rainy day fund for unforeseen larger expenses, and pay a fixed amount towards paying down the startup costs each month. Any funds left over after that are distributed through Cobudget, a simple software platform for people to propose things to do with the funds. Current ideas include buying a piano and boosting sales of one resident’s recently released novel.

If you need funding for something that is clearly necessary for communal life — toilet paper, garbage bags — our default at Gramercy House is that if it’s under $50, you should purchase it and request reimbursement from the house account automatically. Anything above $50 must be run by the other residents before spending the money. Purchases that are nice to have but not necessary — board games, fancy kitchen appliances — don’t qualify for reimbursement, but can be bought with Cobudget funds.

Many communes have a non-resident membership option, for people who wish to contribute to the house and take advantage of common resources without living there. David Witkin of the Red Victorian describes one model:

The Red Vic has a “citizenship” application, for those who don’t want to live here but still want to be a part of our community, which gives them the option to join our committees, get priority tix for our events, and pay into our Food Fund, esp if they are here frequently, among other perks. Non-resident significant others are a perfect example of candidates for citizenship.

The Red Victorian also has a detailed breakdown of operating costs on its wiki.

How much does it cost to start a commune?

Startup costs may include a broker’s fee, a deposit, down payment if you’re buying, legal expenses associated with setting up an entity to manage the property, and furnishing.

In an ideal world, you have a group of people who are all able to sign a lease and commit to splitting expenses evenly upfront. In practice, coordinating this is nearly impossible, especially as you scale the number of rooms. What often ends up happening is that a founding team fronts the money to secure a lease and furnish the commune. Unless they are rich and selfless, the founding team will probably seek to recoup this cost over time by charging a slightly higher rent to future housemates — which is fair, since those future housemates don’t have to pay a broker’s fee, furnish their rooms, or take on the risks associated with the lease.

As an example: a 15 person commune in San Francisco had startup costs of $100k, which was fronted by 3 founders as a loan with 5% interest. The loan repayments were factored into house costs so that $2k went to paying down the loan every month, giving a repayment time of just under five years.

What happens to excess cash after the startup costs are repaid? That’s up to whoever controls the lease. They can decide to reinvest it in the house by lowering all rents, putting the money towards upgrades, or keep it as income. The latter has tax implications that vary by state, and goes against the ‘profits profit the community’ principle I outlined in my definition of commune above.

What happens if a founding member wants to move out before the startup costs are recouped? We didn’t plan for this at Gramercy House, and it led to acrimony when one founding member decided to leave the house after a year and insisted on being repaid first, despite us all being in debt from the upfront costs. We’ve seen this settled more amicably when the departing founder is willing to take a discount on the outstanding debt and/or simply be repaid over time, even if he or she is no longer living in the house.

Another way to spread the risk and cost would be for incoming housemates to buy into the startup debt, similar to how they might pay a broker’s fee, and then enjoy gradual repayment proportional to their percentage of the remaining debt. Again, all this will have legal and tax implications that are best addressed on a state-by-state basis.

How do you control decision making?

Most communes I know operate by do-ocracy, an organizational structure in which individuals choose roles and tasks for themselves and execute them. In other words, if you think the fridge is dirty, you clean it, or hire/delegate someone to do it. This way of operating is faster than consensus based (‘let’s have a meeting and assign responsibilities together’, yawn) and more inclusive than a ‘founders/lease holders decide everything’ situation.

Zarinah Agnew has has written extensively (and amusingly) about the Embassy’s experimentation with governance structures, why they settled on do-ocracy, and three simple rules for implementing do-ocracy in your home:

- Transparency means letting people know what’s happening, in a way that they can get involved if they want, and if not, allows you to proceed knowing they are informed.

- Communication means inviting feedback before taking action.

- Reversibility — The threshold of taking doocratic action is reversibility; that is, only take unilateral action if your action is reversible, and you are happy for others to iterate on or disagree with your decision. Otherwise, wait for feedback and consent.

How do you communicate day-to-day?

Since Gramercy House is relatively small and has low turnover, we use Whatsapp for day-to-day communication, a shared Google calendar, and email. Larger communes tend to default to Slack for internal communication. Modern Nomad, the software platform designed by the Embassy Network, makes it easy to coordinate comings and goings, propose and collect RSVPs for events, collect rent for rooms, and share what you’re doing with the wider world.

How do you deal with significant others?

Some communes explicitly bar members from dating, due to the risk of interpersonal conflict that can affect the stability of the commune. I think that if you’ve selected your co-residents well, dating within the house should by default be ok, and people should be trusted to be adults and treat each other well regardless of their romantic status. It also seems natural that you might end up attracted to someone else who shares your values and you see often. In one of the communes I lived in, two residents met and married each other.

When a resident has an outside romantic partner who starts sleeping over regularly, there comes a point where that person should start chipping in to house expenses, especially if he/she routinely uses the common space. If he or she wants to move in, the couple should have a contingency plan for what happens if they break up. One that seems fair and has worked in practice:

- if it’s an amicable break up, the couple decides who gets to stay. I’ve seen couples continue to share a room platonically post breakup until another room in the house opens up.

- if it’s contentious, both have to move out, even the person who was the ‘original’ member of the community. This saves the community from having to choose sides, but is really hard on both individuals.

How do you kick people out?

You and I might think that bringing someone home at 3am and turning on loud music is not a very nice thing to do to your roommates. Or you might never dream of leaving your dirty dishes out for days, to the point that they provoke an ant infestation. Ninety percent of the people who have stayed at Gramercy House have understood this intuitively, but very occasionally, otherwise well-adjusted people turn out to be total PITAs in their living space.

To guard against this, we have a one page code of conduct that we ask everyone to agree to before they move in. Thankfully, people who have trouble adhering to these rules generally understand they’re not a good fit, and have moved out peacefully. Beyond that, we always make sure to have people sign a lease, and we have occasionally declined to renew leases for people who don’t explicitly violate the code of conduct but are otherwise not a great fit.

For communes where everyone is an adult and you have a good vetting process, an informal agreement is probably fine, but as the stakes go up it makes sense to have a formally binding legal contract that has been negotiated well before shit hits any fans. A commune in Oakland that consists of three couples who aim to raise their kids together in the 7-bed home they were able to purchase by pooling funds has what they call a ‘meth clause’ in their legal documents — an agreement for what should happen if a member becomes destructive to him or herself and the community. When you’re dealing with hundreds of thousands of dollars in investment and children’s safety, a couple thousand dollars in legal fees upfront is worthwhile insurance.

Redux: Why would you choose to live this way?

Sharing your personal space and life with other people is always a risk. If you’re fortunate enough to have made enough money to be able to live on your own, it might seem crazy to instead choose a situation where you don’t know who or what awaits you when you get home. What if you come home at the end of a long week wanting to relax but find your roommates are hosting a dinner? What if you want to make a lot of noise banging on a set of drums or, well, banging your partner(s), without worrying about disturbing other people? What if another resident makes a bad judgment call and lets someone into the space who steals something or, worse, poses physical danger?

Commune life is never going to be perfect. Mistakes are made, feelings and people can get hurt. But what life doesn’t carry those risks?

What if you come home at the end of a long week and find a healthy, home cooked meal waiting for you? What if you want to make a lot of noise and your house has prioritized building a studio space so that you have the freedom to do that, no matter the hour? What if another resident brings home a friend with whom you fall in love and live happily ever after?

Every day, we have the option to stay in small, familiar, safe spaces, or expose ourselves to the possibility of something greater. There’s something satisfying in even the attempt. You may risk discomfort or disappointment, but you’ll never wonder what might have come your way if you’d left the door open.

Additional resources:

- The Embassy’s Wiki, full of useful operational info

- More info on Cobudget

- Death in the Co-op Family, a paper on how or why communes sometimes fall apart